Background. This piece is based on an article published in the early 1980s. Aside from a few textural amendments, it is re-produced here in its original state. That being the case, it needs to be recognised that the Army has changed much since the article first saw the light of day. Readers, if any, should appreciate that some of the content relates to another article that is not available here; it also relates to another age, hence women do not feature.

************

I have a belief – probably totally unjustified – that most articles in this military journal concern ‘things’ rather than ‘people’. Few who are aware of my academic background would disagree with my claim not really to understand ‘things’. It is no surprise therefore that I should be attracted to articles about people. Thus it was that my attention was directed to a Regimental Sergeant Major’s (RSM) interesting piece in the last issue.

The RSM’s article has provoked this response with its attendant release of heresies. But before revealing my hand, I will be imprudent enough to take issue on two matters he raised:

- The Command Post Officer CPO. In my experience the ex-No l of a gun frequently becomes a better CPO than his ex-Technical Assistant Royal Artillery (TARA) Sergeant counterpart. The RSM alludes to one of the reasons in the article – i.e., the ambitious capable soldier, ‘conscious of the good promotion prospects, opts to serve on the guns’. Second the ex-No 1 has a far clearer understanding of the problems on the gun line and third there is a broader recruiting base. (In making these points I do not seek to denigrate the TARA Sergeant).

- Boredom. We need to be conscious of the dangers of boredom at one end of the spectrum and of an over controlled environment at the other: both are extremes and.there is a need for balance. I suspect that the ‘management’, sometimes for commendable reasons, underestimates the capacity of soldiers to enjoy themselves constructively. After all today’s soldier is educated, well paid, frequently owns a car and, in many cases has well developed interests – not just in the opposite sex.

The term ‘controlled environment’ has a ‘big brother’ aroma to it and, sadly, enlightened despotism can too often lead to plain despotism. (One ridiculously amusing, but true, example of this well meaning zest for control concerns the Battery Sergeant Major (BSM) of my first Battery who left an ‘O‘ Group (Orders Group) in a hide position, woke up the somnolent soldiers, and told them to ‘get their heads down’). The ‘put on a pair of boxing gloves’, ‘go for a run’ or ‘have a thrashing game of rugby’ syndrome is dying hard. Indeed does this panacea for the bored soldier persist because of the management’s concern for its collective career?

Business is a laudable watchword but the management must gamble a bit and allow the Gunner[i] some freedom of choice on the direction of his activities. These thoughts are aimed at the need for a sensible balance between total disregard and over supervision. In my first Regiment the latter view prevailed and, to avoid boredom, Saturday morning work was the norm. Such industry invariably resulted in some nugatory pottering around the Gun Park before we retired to the Battery Bar – for obvious reasons the rest of the day was a write off. Thus the comatose soldiers caused no problems and management careers prospered!

The Royal Artillery Officer In Particular

Despite the broad title and the wide ranging content of the RSM’s article, it really considered the soldier rather than the officer. My intention is to widen the net to include the officer but before so doing it must be said that these observations are sometimes emotional rather than factual and that, in keeping with my reputation, no research has been undertaken – hence the title of this piece. These emotions focus on the following syndromes and/or factors:

- The Posting Cycle

- The Regimental Spread

- The Thinking Two Up’ Syndrome

- The Officer Shortage

- Career planning.

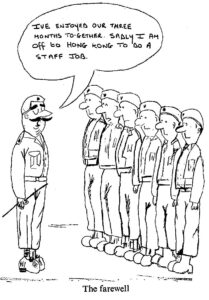

The Posting Cycle. Gunner officers change units every 2-3 years (for my purpose I will ignore the few exceptions to this observation). Further, their time in a Regiment is frequently interrupted by protracted absences and complicated by intra-Regimental changes of appointment. Such a sequence must surely disrupt the soldier and hamper the development of a trusting relationship between him and the officer. I am reminded of the valedictory address of a Battery Commander (BC): ‘It has taken me two years to knock you into shape and I can now confidently hand over an efficient Battery to my successor’ which was followed some two weeks later with these words from his successor: I have watched you closely over the past two weeks and I believe it will take me at least a year to knock you into shape’. This see-saw pattern must confuse the soldiers, however well-intentioned such utterances are meant to be.

In the lead up to any handover there is inevitably a period where decisions are either held in abeyance in fairness to a succeeding Commander or, more cynically, rushed through at an ill-judged speed to beat the deadline. Of course every Commander will rightly bring with him fresh ideas and a new approach – perish the thought of returning to the days of Fuller’s Military Monks. Further, I do accept that new ideas are one of the strengths of these changeovers and that the rapidity is not unique to the Regiment. But in comparison to the Royal Armoured Corps (RAC) or the Infantry, they are greater obstacles in our path to developing a ‘family spirit’. Indeed many of us can attend four to five regimental reunions which, numerically, may be regarded as too many to talk of a family. Whatever became of those ‘lasting’ friends I made in my first regiment? Tracking the whereabouts of my contemporaries in the Blue List[ii] is a poor substitute for the friendships we once had.

Perhaps of deeper concern, is the possible exploitation of the posting cycle by the unscrupulous officer. It must be a considerable temptation to place great demands on the soldiers in the interests of career profit, in the knowledge that the long term impact of such cynicism will result in no personal repercussions. Soldiers are loyal, tolerant and not given to mutiny; they will circumvent exploitation and with over one million unemployed their tolerance is inevitably greater at the present time. In contrast, despite some dilution resulting from the Divisional system, the Infantry officer joins a family circle, develops into a mature leader over the years, grows older with his soldiers and, perforce, takes a long term view of the interests of those under his· command. (The RAC is in a similar position and I have often wondered if this family relationship is why so many senior Gunner officers’ sons appear to have joined armoured regiments).

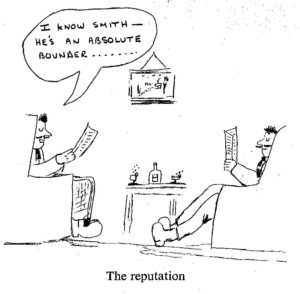

The posting cycle can equally have an unfortunate impact on an officer’s career. First, during his tour of duty an officer may serve under two Commanding officers both of whom have met him from ‘cold’ (i.e. no residual personal knowledge exists); a Commanding Officer’s judgement must be coloured by the views of others -perhaps even before command is assumed. Sadly, in a highly competitive world, first impressions count for much and they may be regarded merely as confirmation of second-hand views. Second, before arriving in a regiment it is likely that an officer’s reputation will precede him at a lower level; often the reputation is based on Mess Bar gossip emanating from others who have known him previously. Incalculable and unjust damage can occur in this way. For example, as a very young officer I was obliged to spend a night in a Gunner Mess en route to a KAPE[iii] tour. In the bar after dinner, those assembled were treated to a character destruction of my troop Commander who was shortly to be posted to the unit concerned. Such an assassination was totally unjust and merely reflected a personality clash.

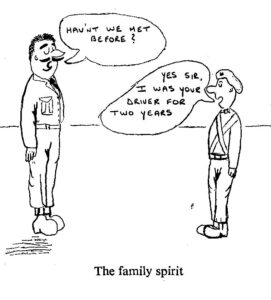

There is no doubt in my mind that the posting cycle militates against the establishment of a happy family atmosphere: it denies the officer corps the opportunity to know soldiers in depth or to handle the latter’s problems with real sensitivity and continuity. Inexorably the pastoral role of the officer is either moving into the hands of the Senior Non Commissioned Officer (SNCO), who offers a stability spawned from continuity, or becoming the province of the semi-professional welfare organization (e.g. SSAFA, the Padré and the Families Officer). Examples always assist in underscoring a point. Some years ago I met a Lance Bombardier (L/Bdr) from my old troop and, uncharacteristically for me, I found myself in a position of total recall, remembering his name, his interests etc. As we parted company, after a healthy discussion, he said ‘By the way Sir who are you?’ The question was a considerable blow to my vanity and, doubtless, many would argue that is was a predictable response to my ineffectiveness as a troop Commander. My interpretation of this inglorious anonymity is that it was spawned from a situation where a young soldier had served under four troop commanders in three years.

The anonymity problem is not confined to the junior officer. I, with several others, witnessed the following conversation between a brigadier and a sergeant who had served under the former’s command:

Brigadier: ‘Good morning Sergeant – good to see you again Sergeant Small.’

Sergeant: ‘Good morning Sir – actually my name is Sergeant Large.’

Brigadier: ‘That’s right. Where did we last meet? Singapore wasn’t it?’

Sergeant: ‘No Sir it was Hong Kong.’

Brigadier: ‘Of course it was. How’s your little boy.’

Sergeant: ‘It’s a little girl Sir.’

The story is both amusing and sad. Quite the most endearing aspect of the incident was that after the brigadier’s departure the Sergeant turned to us and said with uncontrollable pride, ‘He remembered me’. As it happens the Brigadier was a good bloke which may have spawned a high level of forgiveness in the Sergeant.

Finally the posting cycle has a deleterious effect on our relationship with the supported arms[iv]. The frequency with which BCs and Forward Observation Officers (FOO) change must not only confuse the Battle Group and Combat Team Commanders but also preclude the development of professional trust.

The Regimental Spread. Some of the effects on officer/soldier relationships which accrue from the posting system, have already been discussed. There are other inter-related aspects which might be more properly considered under the heading of the regimental spread. Officers not only change regiments but in many cases move to a new discipline (e.g. from Field Artillery to Air Defence or even Locating). Some would argue, with considerable justification, that such a broad base of knowledge is essential since the majority of officers away from the gun position have the remit of advising supported arms commanders[v] on all aspects of the Regiment’s capabilities. It is a daunting remit which becomes more complex with each technological advance and with every increase in the number of Gunner cap badges in the Battle Group Area. In consequence significant professional demands are placed on the young(er) officer who, for example, in the Field Artillery discipline is required to master the roles of CPO, FOO and the Gun Position Officer (GPO) in a few short years (this could be further complicated by a tour as Adjutant or Signals Officer).

With job changes of such frightening rapidity does the officer truly gain a satisfactory professional knowledge or is his expertise a superficial veneer? Does he survive Practice Camps by a combination of good fortune and the support of highly professional soldiers? Should we be surprised if the same professional soldiers are not exactly overawed by our technical expertise or that the conscientious officer is a bit serious?

It is not difficult to have sympathy for a dedicated officer who is striving to attain a high level of technical proficiency as well as looking after the needs of his soldiers. He must at times feel that the system militates against the successful conduct of his duties. In particular the compressed time scale of experience and training of a graduate entry is most deserving of sympathy. Perhaps we are witnessing the demise of the rank of

Second Lieutenant (2/Lt); the graduate officer is quickly promoted to a rank which belies his knowledge or experience. Does the experienced NCO, who traditionally put a young 2/Lt on ‘the right track’, find such an advisory role more difficult to implement with today’s captain of yesterday’s 2/Lt’s experience?

Thinking Two Up Syndrome. No doubt the PQS[vi] curriculum exhorts an officer to develop a professional knowledge of the next rank up. But in this section I am considering the ability to impress rather than the laudable requirement to be ready to fill somebody else’s shoes at short notice. I would not, pretend that the desire to impress our seniors is a peculiarity of the Regiment, indeed having witnessed the cut and thrust of the Army’s outside world, I believe that Gunner officers are less RADA-orientated than most. But in truth can we all claim that our efforts are geared to the interests of our soldiers rather than impressing, or dare I say it, hoodwinking our superiors? Of course every officer is required to be something of an actor (we learn that at the Regular Commissions Board[vii]).

At the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst (RMAS) the need to think two up was a principle drummed into Cadets, so a Lieutenant would be thinking about the duties of a sub unit commander – a Major. Thus, even at RMAS our military education embraced consideration of the roles of both platoon and company commanders. Such thinking made absolute sense in terms of war planning since casualties might create vacancies up the chain of command. In peacetime however, the ambitious officer considered thinking two up to mean impressing the boss’s boss; thus a Major would hope to catch the eye of a Colonel or Brigadier. In fairness to the ambitious, the reporting system encourages such thinking since the unseen contribution to a Confidential Report by a Senior Reporting Officer (SRO) – the Colonel or Brigadier – can make or break a career[viii]. Of course, the Gunners operationally function on the thinking two up principle with a Major BC advising the Commanding Officer of a RAC regiment or a battalion. In peacetime however, outside that operational remit, other cap-badges are more adept than the Gunners at thinking two up in the interests of career progression.

The Staff Factor. The sublime position of the staff remains unchallenged. Officers are frequently short toured to be removed from the regimental coal face in the interests of the staff machine. For some inexplicable reason it is apparently more acceptable for a unit to bear a shortfall against its establishment; could this be the de facto recognition of the increasing dependence on the Senior NCO? Of course, it would be wrong to over simplify the arguments on this clash of priorities and certainly inappropriate to suggest that the staff is superfluous! Equally I am convinced that there is scope for improving the efficiency of the staff with a consequential reduction in manpower. For example are we properly utilising the array of business machines at our disposal? Do we need 40 staff officers in the MOD simultaneously drafting written briefs for their masters on the same document? But I digress!

The loss of a good troop· commander to a junior staff appointment is difficult to explain to the soldiers. The officer understands only too well that his move is an important step towards his particular chair on the Army Board. So, such a removal of talent represents another disruptive influence at the coal face and it is difficult to convince the soldier that he is really the exalted one.

Officer Shortage. Now that we are well into the complex age of mechanization, battery strengths seem to have reduced in tandem·. Unless I am the victim of some senile illusion, I am sure that the strength of a towed 25-pounder battery was significantly larger than its Abbot Self Propelled counterpart. The increased complexity of the equipment combined with the reduction in strength has resulted in more work and less play at all levels. No longer does a battery have a carpenter or a runner.

With the contraction in overseas postings and the consequential commitment to the eternal triangle of BAOR, GB and Northern Ireland, there has been a further reduction in the opportunities for play. The reduction in play is exacerbated by the seemingly endless round of important inspections and the progressive pressures of the training cycle. Commanding Officers understandably want their first elevens in situ during these peak periods (or is the peak a constant?). Under such circumstances can a junior officer be spared to take his troop away for a couple of weeks? Who bears the burden · of the orderly officer roster in his absence? Who takes over his account? etc etc. In practice certain officers do get away although perhaps not with their soldiers. Unfortunately these escapees tend to be the established gladiators in their particular field.

Nobody would suggest that most walks of life today are not highly competitive. The Army reflects society, albeit with a built-in time lag, therefore we must accept the inevitable diminution of fun and, perhaps, that the modern young officer is different to his predecessor. Against this background today’s subaltern is deserving of much sympathy from an older generation which was allowed time to enjoy itself and mature before being enveloped by the career spectre. I am not convinced that such sympathy obtains. Too often today’s junior officer is regarded as dull; who or what made him thus?

Career Planning. Few would dissent from the view that the British Army is the most professional in the world. Competitiveness, with its consequent seriousness, is one of the prices to be paid for such a reputation; the need for career planning is another. My worry is that career planning starts too early which is another factor in lowering the earnesty threshold. There are tremendous pressures to get it right-first time! The idea of learning by mistake is at best dormant at worst deceased. Indeed for every officer who errs there are another ten who have not; why · should the reporting system take detailed account of a mistake? Subalterns are striving for outstanding reports from the outset and planning for their first staff appointments as they are smothered by the seemingly endless array of mandatory courses. This perpetual cycle of education necessitates further absences from regimental duty and it may ultimately help to develop an officer corps which is little more than civil servants in khaki. Service life becomes serious enough with each successive promotion and there is surely no requirement to accelerate that process. The earmarking of today’s subaltern for tomorrow’s Army Board takes little account of the late developer who frequently served us so well in the past.

Before returning to some further thoughts on the officer in absentia, two stories are offered which represent the gulf between ancient and modern. The first is a manifestation of the ‘get it right first time’ syndrome. Some years ago I attended the pre-BATUS[ix] brief during which a particular briefer stated that the commander of a unit or sub unit which did not do well should abandon any hope of a successful career. Is that really the way to engender enjoyment from training? The results of such attitudes are well known – we now train for training!

The second story relates to a very senior officer whose regiment produced a considerable number of successful contemporaries. He explained that the collective success had accrued from regimental policy. On joining his regiment the Commanding Officer instructed him to live life to the full, look after his soldiers and not worry about his confidential reports (the implication being that they would be more than adequate). The quid pro quo to this liberal exhortation was that he must pass the Staff College exam – he did!

Now to return to the absentee officer. Predictably, to furnish my emotive style, I will look again at the graduate officer. On arrival he will be older than his fellow subalterns but the differential is soon made good through back dated promotion. His wild oats phase is probably behind him and he had the advantage of sowing them away from the watchful eyes of a Commanding Officer. He moves quickly through the subalterns’ appointments to captain – perhaps an Adjutant. Throughout this smooth progression he will have attended a miscellany of appropriate professional courses (Young Officer, CPO, GPO, Junior Division of the Staff College, Military Law etc). So, with minimal soldier contact he is probably being groomed as tomorrow’s senior Gunner (said without rancour since I am not anti-graduate).

Perversely the system argues against a Staff Corps on the grounds that adequate regimental experience is essential to the efficacy of a staff officer. I regard the argument as fallacious in that one quickly forgets the problems of regimental soldiering – remembering with selectivity the good times and the ease with which problems were solved.

Conclusions

The foregoing unsubstantiated, perhaps unpalatable, thoughts may merely represent a release of steam. But a price must be paid for the luxury of such an outburst and the military machine dictates the need for some conclusions lest I am accused of making of factitious comment (as Disraeli opined ‘It is easier to be critical than to be correct’). However I will resist the need for detailed conclusions and confine myself to impressions of certain ‘danger areas’:

- The scope for the cynical officer to progress with impunity.

- The inadequate opportunity for officers truly to manage their soldiers, perforce linked with the increased dependence on the Senior NCOs who provide continuity of management and leadership

- The difficulties of developing a satisfactory professional relationship with the supported arms.

- The premature injection of ambition into junior officers’ lives with an attendant diminution of fun; such degradation of fun potential is exaggerated by an apparent officer shortage.

- The erosion of the importance of regimental duty by the pre-eminent position of the staff.

- A need to ‘get it right’-first time which discourages delegation.

- Confusion amongst our soldiers.

[i] In this context, the Royal Artillery equivalent of a Private soldier.

[ii] An erstwhile document of great value in terms of keeping in touch with serving an retired officers. For the ambitious officer it offered an insight into the competition since the data included dates of birth (DOB) and promotion opportunities were generally linked to the DOB. It seems that GDPR killed off the product.

[iii] Keeping the Army in the Public Eye. Such tours were, superficially, a PR exercise but with the underlying, generally forlorn, hope of actually recruiting someone.

[iv] The Royal Armoured Corps (RAC) and the Infantry (Inf).

vi] With apologies, I can no longer recall the meaning of PQS; the only definition Google offers is: The Pharmacy Quality Scheme. I can assure any reader that PQS in this article has nothing to do with the pharmaceutical sector.

[vii] The RCB is/was the initial interview process for joining the Army as an Officer, either for RMAS or Mons, the latter, initially at least, was for Short Service Commission Officers. For me, thankfully, the experience proved to be far less demanding than the Admiralty Interview Board (AIB). I say ‘thankfully’ since, had the Army not accepted me, I might have spent a miserable life in the Return Premiums of the Commercial Union Insurance Co.

[viii] Since the implementation of the Freedom of Information Act this hidden method of secretly ruining an officer’s career is presumably much more difficult to achieve perhaps even impossible – here’s hoping.

[ix] British Army Training Unit Suffield in Canada.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.